Dec, 21 2025

Dec, 21 2025

Most people think of tuberculosis as a disease you catch and immediately get sick. But that’s not how it usually works. In fact, the majority of people infected with TB bacteria never develop symptoms. Their bodies lock the bacteria away-quietly, invisibly-for years, sometimes decades. This is called latent TB infection. It’s not contagious. You feel fine. You don’t cough. You don’t know you have it. But if your immune system weakens, that hidden infection can wake up and turn into active TB disease-a serious, contagious illness that can damage your lungs and even kill you if left untreated.

What’s the Difference Between Latent TB and Active TB?

Latent TB means the bacteria are alive but asleep. Your immune system has built walls around them-tiny clusters called granulomas-that keep them from multiplying. You won’t feel sick. You won’t spread it to anyone. Your chest X-ray looks normal. The only sign you have it? A positive skin test or blood test (IGRA). About 30% of people exposed to TB develop this latent state. But only 5-10% of them will ever turn it into active disease. That number jumps to 50% or more if you have untreated HIV, diabetes, or are on immunosuppressant drugs.

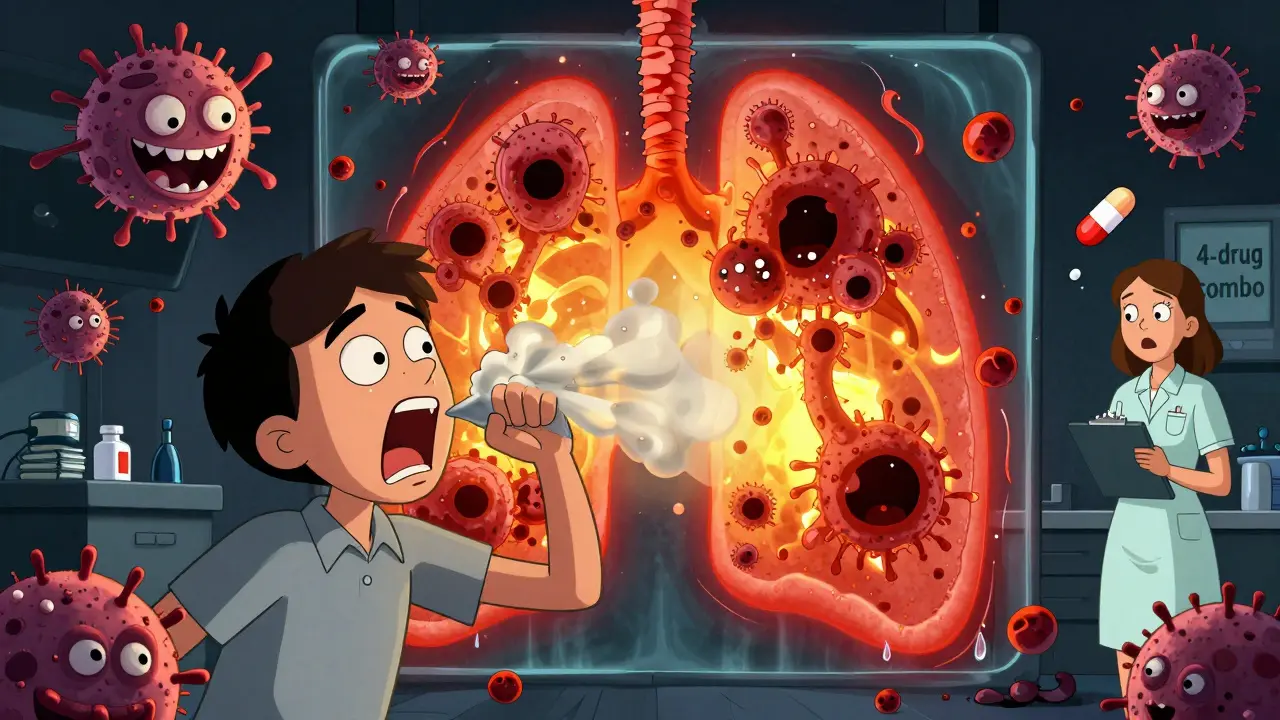

Active TB is the opposite. The bacteria have broken free. They’re multiplying, eating through lung tissue, and triggering inflammation. You’ll start feeling it: a cough that won’t quit-lasting more than three weeks. Night sweats so bad you need to change your sheets. Fever that comes and goes. Weight loss without trying. Fatigue that sticks to you like glue. Some people cough up blood. Your chest X-ray will show shadows or holes in the lungs. And here’s the critical part: you can spread it. When you cough, sneeze, or even talk, you send infectious droplets into the air. Someone breathing those in can get infected.

How Do Doctors Diagnose TB?

If you’ve been exposed or come from a country with high TB rates, your doctor will test you. The first step is always a skin test (TST) or blood test (IGRA). A positive result means you’ve been infected at some point. But it doesn’t tell you if it’s active or latent. That’s where the chest X-ray comes in. If it’s normal, you likely have latent TB. If it shows damage-patches, cavities, fluid-you’re probably dealing with active disease.

For active TB, doctors need proof the bacteria are alive and multiplying. That means testing your sputum. They’ll ask you to cough up mucus from deep in your lungs. The sample gets sent to a lab. If the bacteria grow in culture (which can take weeks), or if a rapid molecular test (like NAAT) detects TB DNA, you have active TB. No sputum? No growth? No DNA? Then it’s not active TB, even if you have symptoms. Other illnesses can mimic TB-pneumonia, fungal infections, even lung cancer.

How Is Latent TB Treated?

Latent TB doesn’t need emergency care. But it does need treatment. Left alone, it can become active at any time. The goal is to kill the dormant bacteria before they wake up.

The oldest and still most common treatment is isoniazid taken daily for nine months. It works, but sticking to it for that long is hard. Side effects like nausea, fatigue, and liver stress make people quit. That’s why newer, shorter regimens are now preferred.

The CDC and WHO now recommend a 3-month course of isoniazid plus rifapentine, taken once a week under direct observation. This is called 3HP. It’s just as effective, but completion rates jump from 60% to over 85%. Another option is rifampin alone for four months. Both are easier to finish than nine months of daily pills.

Who should get treated? People with HIV, recent TB exposure, diabetes, kidney failure, or those taking biologics for autoimmune diseases. Kids under five with positive tests. People who’ve had organ transplants. If you’re in one of these groups, treating latent TB isn’t optional-it’s life-saving.

How Is Active TB Treated?

Active TB is a medical emergency. Left untreated, it can destroy your lungs, spread to your spine, brain, or kidneys, and kill you. It also spreads to others. Treatment must start immediately.

The standard first-line treatment is a four-drug combo: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. You take all four for the first two months. This is called the intensive phase. It kills the bulk of the bacteria fast.

Then comes the continuation phase: just isoniazid and rifampin for four more months. Total treatment: six months. Some cases-like TB in the spine or brain-need up to nine months.

Why four drugs at first? To prevent drug resistance. TB bacteria are sneaky. If you use just one or two drugs, the ones that survive mutate and become untreatable. Using four at once crushes their chances.

But here’s the catch: these drugs can hurt your liver. Your doctor will check your blood every month. If you get yellow eyes, dark urine, or severe nausea, call your clinic right away. You can’t just stop the meds because you feel better. Stopping early is how drug-resistant TB is born.

What Is Directly Observed Therapy (DOT)?

Active TB treatment is long, complex, and risky if not done right. That’s why health departments use DOT. A nurse, community worker, or even a family member watches you swallow every pill. They log it. They remind you. They catch problems early.

DOT isn’t about control. It’s about survival. In places like Brisbane, DOT is standard for all active TB cases. Why? Because one person stopping treatment can create a strain of TB that no drug can kill. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) is harder to treat, takes two years, costs 100 times more, and has a 50% death rate. DOT cuts that risk by 90%.

Why Do Some People Never Get Sick?

Science still doesn’t fully understand why some people’s immune systems lock TB away forever, while others’ bodies fail. But we know it’s not just about strength. It’s about balance. Research shows that in latent TB, your immune system uses a specific type of T-cell-CD8-that keeps the bacteria in check without wiping them out. In active TB, those cells are overwhelmed, and other immune responses go haywire, causing more damage than the bacteria themselves.

Some experts believe there’s a spectrum-not just two states. Maybe you’re not fully latent or fully active. Maybe you’re somewhere in between: low-level bacterial activity, no symptoms, no transmission, but your immune system is constantly fighting. That’s why some people develop active TB years after exposure, even without HIV or other risks. Their immune system just got tired.

What’s New in TB Treatment?

For decades, TB treatment hasn’t changed much. But now, things are moving faster. The WHO now recommends the 3-month 3HP regimen for latent TB in most countries. New drugs like bedaquiline and delamanid are helping treat MDR-TB, though they’re expensive and not yet standard everywhere.

Researchers are testing shorter active TB regimens-four months instead of six. Early trials look promising. There’s also work on vaccines. The old BCG vaccine only protects kids from severe forms of TB, not adults from lung disease. New candidates are in phase 3 trials. And scientists are exploring drugs that don’t kill bacteria but boost your immune system to do it better-called host-directed therapy.

But the biggest breakthrough isn’t a drug. It’s screening. Finding latent TB in high-risk groups-refugees, homeless populations, people with HIV-before it turns active. That’s where public health wins. Treating 100 people with latent TB prevents 5-10 cases of active TB. That saves lives, money, and stops chains of transmission.

What Happens If You Don’t Treat TB?

Latent TB? It might never bother you. But it might. And when it does, it’s harder to treat. Active TB? It won’t go away on its own. It gets worse. Your lungs scar. You lose weight. You can’t breathe. You cough blood. You can’t work. You can’t care for your kids. You become a walking source of infection. And if you stop treatment early? You create a monster: drug-resistant TB. That strain can spread to your partner, your child, your coworker. And once it’s out there, it’s nearly impossible to cure.

TB kills 1.3 million people a year. Most of them could have been saved with early diagnosis and full treatment. It’s not a disease of the past. It’s still here. In Brisbane. In Manila. In Johannesburg. In every city where people live close, work hard, and can’t always access care.

Can you catch TB from shaking hands or using the same toilet?

No. TB spreads only through the air when someone with active lung TB coughs, sneezes, or sings. You can’t get it from surfaces, food, or skin contact. Being in the same room for hours with an untreated person is the real risk-not a quick handshake.

If I had a positive TB skin test years ago and never took treatment, am I still at risk?

Yes. Even if you felt fine, the bacteria are still there. Your immune system may be holding them back now, but if you get sick, stressed, or older, your defenses can weaken. That’s when latent TB wakes up. It’s never too late to talk to your doctor about testing and treatment.

Can you have TB without coughing?

Yes. While lung TB causes cough, TB can infect other parts of the body-lymph nodes, spine, kidneys, brain. These forms don’t cause cough but can cause pain, swelling, or neurological symptoms. They’re harder to diagnose and often missed.

Is TB curable?

Yes, if caught early and treated fully. Latent TB can be cured with 3-9 months of pills. Active TB can be cured with 6-9 months of multi-drug therapy. But if you don’t finish the treatment, or if you’re infected with a drug-resistant strain, cure becomes much harder-and sometimes impossible.

Can I go to work or school if I have latent TB?

Yes. Latent TB is not contagious. You can work, hug your kids, go to school, and live normally. You don’t need to be isolated. The only time you need to stay home is if you have active TB-until you’ve been on treatment for at least two weeks and your doctor says you’re no longer infectious.

Are there side effects from TB drugs?

Yes. Isoniazid and rifampin can cause liver damage. You might feel nauseous, tired, or get yellow eyes. Rifampin turns your urine orange-harmless, but startling. Pyrazinamide can cause joint pain. If you notice anything unusual, call your doctor. Don’t stop the pills without talking to them. Most side effects are manageable and go away with time.

What Should You Do Next?

If you’re from a country with high TB rates, or if you’ve been in close contact with someone who has active TB, get tested. Even if you feel fine. Latent TB is silent. Active TB is deadly. But both are treatable.

If you’ve been diagnosed with latent TB, take the treatment seriously. Don’t skip doses. Don’t stop early. The 3-month option is easier-but only if you finish it.

If you have active TB, follow your DOT plan. Let the nurse watch you swallow the pills. It’s not a punishment. It’s your best shot at living a full life-and keeping others safe.

TB isn’t a myth. It’s not gone. But with the right tests, the right drugs, and the right support, it can be stopped. Before it stops you.

Sam Black

December 22, 2025 AT 01:53TB is wild because it’s like a sleeper agent in your body 😮💨 I had a cousin in Delhi who tested positive for latent TB but never took meds-now she’s got MDR-TB after a stress-induced breakdown. It’s not just about pills, it’s about how life cracks you open. We need more screening in low-income communities, not just after someone’s coughing blood.

Aliyu Sani

December 23, 2025 AT 17:14latent TB is the silent pandemic no one talks about. you got the granulomas holding it down like a prison guard, but one cytokine storm and bam-active disease. it’s not about strength, it’s about homeostasis. our immune systems are running on borrowed time, especially with chronic stress, poor sleep, and processed food diets. we treat symptoms, not root causes.

Kathryn Weymouth

December 24, 2025 AT 07:38Just wanted to clarify something: the 3HP regimen (isoniazid + rifapentine) is recommended for latent TB in adults and children over 2 years, but it’s contraindicated in pregnancy and severe liver disease. Many providers still default to 9 months of isoniazid out of habit-even though the shorter regimen has higher completion rates. Education gaps in primary care are real.

Tony Du bled

December 25, 2025 AT 02:48Been to Nigeria last year. Saw a guy in a Lagos clinic with TB and no shoes. He was on DOT, nurse came daily with his pills. No drama. Just quiet dignity. TB ain’t some sci-fi horror. It’s poverty wrapped in a cough. We got fancy drugs but still can’t get pills to people who need them. Fix the system, not just the bacteria.

Jamison Kissh

December 26, 2025 AT 02:17It’s fascinating how TB exploits immune balance. The CD8 T-cell mechanism isn’t just about killing-it’s about containment. Evolutionarily, maybe the body learned that wiping out every pathogen isn’t always optimal. Some microbes become part of the ecosystem. TB might be a ghost we’ve learned to coexist with… until we don’t. What if latent TB isn’t a flaw, but a compromise?

Kiranjit Kaur

December 26, 2025 AT 08:14My aunt in Mumbai got diagnosed with latent TB after her diabetes diagnosis. She did the 3-month 3HP and finished it. No drama. No side effects. She’s alive today because someone listened. If we treated latent TB like we treat prediabetes-with urgency, not indifference-we’d save millions. This isn’t just medicine. It’s justice.

Cara Hritz

December 27, 2025 AT 02:23Wait so if you have latent TB you cant spread it but you can still get active later? So like if you get stressed or sick it just wakes up? That sounds like a horror movie plot. Also i think the 3HP thing is just a marketing gimmick, why would they change it if the old way worked? I mean come on. Also i heard rifampin turns your pee orange?? That seems fake.

Gabriella da Silva Mendes

December 28, 2025 AT 12:30Ugh I’m so tired of this TB stuff. Like, we got vaccines for everything else, why is this still a thing? It’s 2025. And why do we have to watch people swallow pills? That’s so un-American. Also, why are we even talking about this? We got bigger problems. Like, why isn’t the government fixing the border? TB is a third-world problem. 😒

Nader Bsyouni

December 29, 2025 AT 02:37Latent TB is just a construct of pharmaceutical capitalism. Who decided that dormant bacteria need killing? Maybe the body knows better. Maybe suppression is the real disease. We pathologize silence. We fear equilibrium. The real epidemic isn't TB-it's our obsession with control. Let the granulomas breathe. Let the bacteria sleep. We are not gods. We are just scared humans with pill bottles.

Sam Black

December 30, 2025 AT 09:04That’s why DOT works. It’s not about control-it’s about connection. That nurse watching you take your pills? She’s not a cop. She’s the only person who remembers you exist. In places with no social safety net, that’s the treatment. And yeah, it cuts MDR-TB by 90%. No magic. Just humanity.